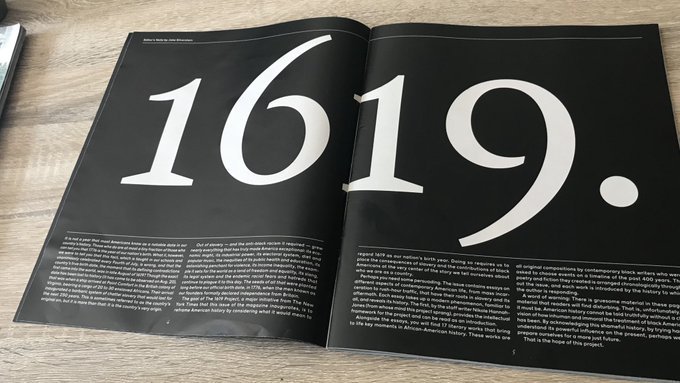

The author of an award-winning biography (Lincoln: A Life of Purpose and Power) and a professor emeritus at Oxford University, Richard Carwardine is hardly impressed with the 1619 project, as he tells the World Socialist Website'sTom Mackaman.

Q. Let me begin by asking you your reaction to the 1619 Project’s lead essay, by Nikole Hannah-Jones, upon reading it.

A. As well as the essay I have read your interviews with James McPherson and James Oakes. I share their sense that, putting it politely, this is a tendentious and partial reading of American history.

I understand where this Project is coming from, politically and culturally. Of course, the economic well-being of the United States and the colonies that preceded it was constructed for over two-and-a-half centuries on the labor and sufferings of slaves; of course, like all entrenched wielders of power, the white political elite resisted efforts to yield up its privileges. But the idea that the 1619 Project’s lead essay is a rounded history of America—with relations between the races so stark and unyielding—I find quite shocking. I am troubled that this is designed to make its way into classrooms as the true story of the United States, because, as I say, it is so partial. It is also wrong in some fundamentals.

I’m all for recovering and celebrating the history of those whose voices have been historically muted and I certainly understand the concern of historians in recent times, black and white, that the black contribution to the United States has not been fully recognized. But the idea that the central, fundamental story of the United States is one of white racism and that black protest and rejection of white superiority has been the essential, indispensable driving force for change—which I take to be the central message of that lead essay—seems to me to be a preposterous and one-dimensional reading of the American past.

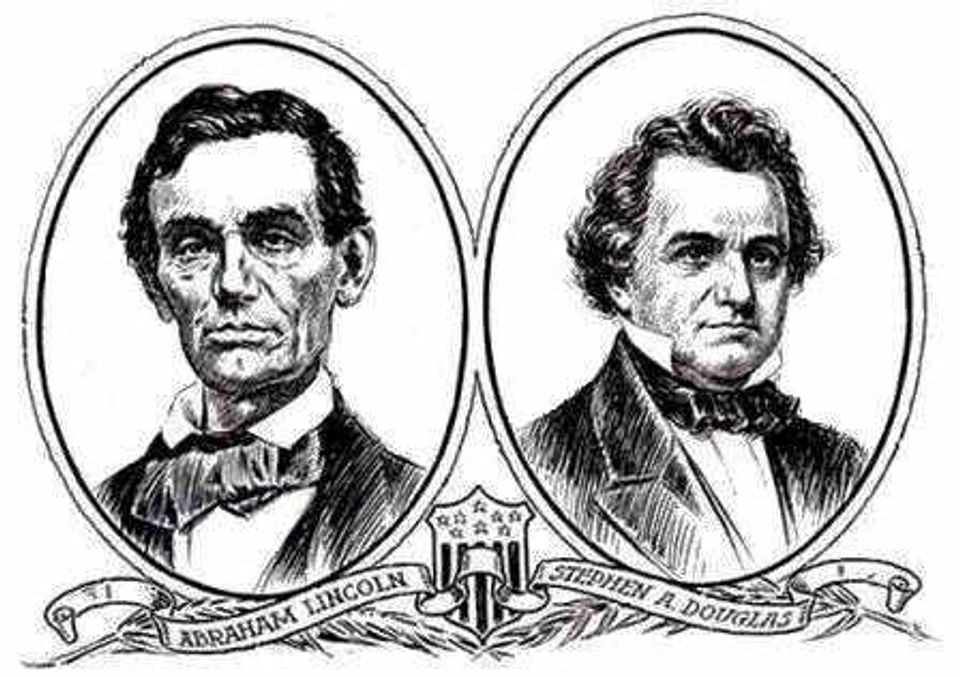

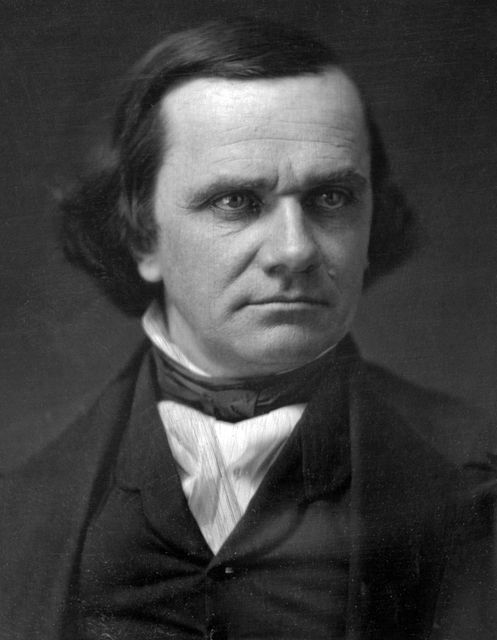

… I am pleased, but not surprised, that some African-American historians are stepping forward to challenge the narrative that appeared in the New York Times .Q. Let me ask you about the treatment of Abraham Lincoln. Nikole Hannah-Jones homes in on two episodes: the meeting on colonization with leading African-Americans in 1862, and the well-known quote from the Lincoln-Stephen Douglas debates in which Lincoln disavows social equality for blacks. Could you comment on these two episodes, their presentation by the New York Times, or situate them in the evolution of Lincoln’s thinking as regards race and slavery?

A. There is indeed an evolution, but first I’ll make two broad points. One is that context is all. Illinois was in 1858 one of the most race-conscious states of the Union. Alexis de Tocqueville concluded that white hostility towards blacks was strongest in the northwestern states. The black laws of Illinois were amongst the fiercest in the country. Lincoln knew that he could not be elected if he were seen as a racial egalitarian. I’m not suggesting he was a racial egalitarian, but we should take into account the political context that prompted his clearly defensive statements, at Ottawa and Charleston, that he was not seeking black political and social equality. Those statements of his are very few in number, grudging, and at times, I think, even satirical—as when he says that blacks are not “equal... in color.”

When Lincoln addressed the issue of slavery in his speeches from 1854 to 1860, he was on strong ground: slavery was widely disliked and the prospect of its spread was unwelcome to his political audience. But on the issue of race the Republicans were vulnerable. Their call for an ultimate end to slavery had to explain the consequence for black-white relations, and that of course made Lincoln extremely vulnerable to Stephen Douglas’s racism, and his assault on Lincoln as the “lover of the black”—though he would have used a worse epithet, wouldn’t he? So, in reality, Lincoln could only win an election in 1858 by making some concessions to the prevailing racial antipathies of whites. These two statements have understandably, and reasonably, attracted attention. They demonstrate that Lincoln, to secure a Republican victory that would advance the antislavery cause, fell short both of what blacks aspired to and of what the small minority of white racial egalitarians endorsed.

It seems to me that what’s really striking, however, is what Lincoln positively demands for blacks at this time. He embraces them within the Declaration of Independence’s proposition that all men are created equal. By “all men” he means regardless of color, and that’s where he gets into a tussle with Douglas. Douglas insisted the Declaration of Independence was never intended to apply to black people, and of course, Lincoln is emphatic that it does. So for me it’s what Lincoln claims for black people that is striking, and not what he says he will deny them.

With the August 1862 episode, again context is important. It’s a very striking meeting and it’s not Lincoln’s finest hour. Both Nicolay and Hay, his secretaries, said that they thought that Lincoln was at his most emotionally on edge and mentally fraught in the summer of 1862 when the Peninsular campaign had ended in failure, when he had determined on the Emancipation Proclamation but was waiting for a military victory to bring it forward, and when there was increasing clamor for emancipation. Both secretaries said that they had never known Lincoln as nervy as he was then.Q. Could you discuss the origins of the colonization idea?

The point I’m making here is that at that time Lincoln was under even greater human strain than ever. He knew he was on the brink of taking the most dramatic, even revolutionary, action of any president. He’s nervous. He can’t see what all the consequences will be, but he knows the consequences of not issuing the Emancipation Proclamation. It will leave the Confederacy with the whip hand.

That startling episode of Lincoln’s discussions with the five African-Americans—the first blacks invited into the White House as equals—should be placed in this context. Buffeted from all sides during one of the Union’s lowest points of the war, Lincoln lost the good humor that commonly lubricated his meetings with visitors. His message to them about the causes of the war, and the advantages of colonization and racial separation, has to be seen also in the context of the daunting prospective challenge of embracing four million former slaves fully into the American polity.

A. Promoting the migration of American free blacks to colonies in Africa took institutional form in the American Colonization Society in 1816. In the main its early supporters were white benevolent paternalists who couldn’t see a positive future for blacks in the United States because of the depth of white prejudice, but part of its appeal was to slaveowners who saw the advantage of ending the troublesome presence of free blacks in United States. In time, it alienated pure abolitionists, who thought it a bromide, and slave-masters, who deemed it the thin end of an antislavery wedge; it won the support of a few black radicals, including Henry Highland Garnet, but most black leaders strongly opposed it.Q. Could you elaborate on that?

… So that would be my way of looking at those two episodes, of 1858 and 1862. And then I would add that those are only two of the episodes that bear on the matter. I could choose other episodes which give a very different perspective.

A. Where in Nikole Hannah-Jones’s reading of Lincoln, and in her wider perspective, is the voice of the greatest of all African-Americans, Frederick Douglass? He doesn’t appear. Douglass was not uncritical of Lincoln: he famously said that the black race were only Lincoln’s stepchildren. But he also came to extol Lincoln, too, as a white man who put him at his ease, treating him as an equal, with no thought of the “color of our skins,” and showing he could conceive of a society in which blacks and whites lived together in a degree of harmony, that racial relationships in the US America were not irredeemably fixed by its 17th and 18th century past.Q. I’m glad you’ve raised Frederick Douglass. I think there’s been, from some quarters, this sort of knee-jerk reaction to any criticism of the 1619 Project, and some of this has been playing out on Twitter, where one person said, “You’re trying to silence black voices.” But one of the ironies is that there are very few historical black voices in the entire 1619 Project. As you say, Douglass isn’t there. Neither is Martin Luther King, whose name appears only in a photo caption. To say nothing of wage labor, or any attempt to present the African-American experience as having to do with masses of actually existing people. Instead, the focus is on white racism as this sort of supra-historical force.

… There are many other examples of Lincoln’s positive views of blacks. You could take his letter to James Conkling in September 1863. Lincoln was invited by Conkling, a Springfield colleague who asked him to go to Illinois to campaign for the fall elections. Lincoln felt he had to stay in Washington, but he wrote a letter for Conkling to read to the Springfield audience … The letter is in part a paean to the bravery of the black soldiers. I consider it his greatest public letter, a powerful statement of how much he admires those African-Americans who have sacrificially taken up arms for the Union.

I’d like to return to what you said about the evolution of Lincoln’s thinking on race. In Indiana and then in Illinois the vast majority of African-Americans that he encountered were uneducated and in menial jobs; they provided the basis for the black stereotypes of the tall tales and ludicrous stories of the time. But once Lincoln reached Washington he found an aspirational black middle class, and in Frederick Douglass he met someone whom he considered his intellectual equal. Add to this the tens and then hundreds of thousands of black sailors and soldiers fighting on behalf of the Union, and it’s no wonder that by April 1865 he was now prepared to advocate for blacks the political benefits of citizenship, including voting rights. These he wanted to extend only to a minority of black Americans—the educated and those in arms—but still this was a step towards the integration of blacks in a multiracial America.

It’s not too much to say that Lincoln was a civil rights martyr. … My concern with the 1619 Project is not that it highlights the often-cited Lincoln remarks of 1858 and the White House meeting of August 1862. They are part of the overall story. They are real and are not to Lincoln’s credit. But they are thoroughly un-contexted, historically deaf, and blind to a broader reality. Which of us would want to be judged on the basis of two snapshots in our lives? If the essence of Lincoln is captured in these episodes, then why does Frederick Douglass, arguably the preeminent African-American of all time, come to admire Lincoln as a great man and leader? Through his successive encounters with Lincoln, Douglass developed a growing respect and admiration for a president who sought to live up to a progressive reading of the principles of the Declaration of Independence—one, by the way, that is very much at odds with the reading of that document in the 1619 lead essay.

A. … Lincoln’s hostility to slavery I judge has less to do with any emotional empathy with the slave and rather more with his profound sense of the injustice of denying to the slaves the product of their labor. “By the sweat of thy brow shalt thou eat bread,” was a biblical text he often invoked in his speeches during the 1850s. So slavery is at odds with the morality, with the ethical principles, of free labor.… Q. … A centerpiece of your scholarship has been the role of religion in the antebellum. Could you discuss this work?

Lincoln … has a profound faith in democracy, in the capacity of informed individuals to consider rationally where their best interests, and those of their community, lie. He encourages and manages this system and its overturning of an older, deferential politics. Lincoln, then, has experience of a society where it is possible to rise above the social status of your birth and to hold the same rights in politics and citizenship as any other man. That’s why Marx and others so admired Lincoln, why Lincoln was the darling of overseas socialists, democrats, and radicals—particularly, those in Europe who had fought and lost in the revolutions of 1848.

A. The drive towards immediate emancipation among the abolitionists of the early 19th century, and particularly during the 1820s and 1830s, owes much to evangelical Protestant fervor. I should say, as an aside in the light of Hannah-Jones’ 1619 essay, that, although there were a number of important and brave black abolitionists, taken as a whole the abolitionist movement of the 1820s and 1830s was largely white—as it unavoidably had to be, given black numbers, status and resources—in its membership, its sources of funding, and its agencies of agitation and propaganda.Q. Could you explain Lincoln’s attitude on religion?

These white reformers were moved by a powerful sense of the equal humanity of blacks, by the idea of a single Creation, and by the doctrine of disinterested benevolence, the outworking of faith through charitable action. Hence, for example, the setting up of Oberlin College, radical and biracial. This urgent thrust towards immediate emancipation surely poses a problem for those who see racial hostility as the ineradicable DNA of white America. So, too, do the targets of the anti-abolitionist mobs in the 1830s. White advocates of emancipation and abolition were prepared to court martyrdom: this was the fate of Elijah Lovejoy in Alton, Illinois. The 1619 approach reads such biracial progressivism out of the country’s history.

My interest in religion developed through studying slavery and anti-slavery. My first book dealt with transatlantic religion in the nineteenth century, and in particular the considerable impact of American revivalists in British churches, especially those of nonconformist traditions. Oberlin’s Charles Finney, for example, the premier revivalist of his day, made two trips to Britain and his lectures circulated widely; they were even translated into Welsh. The Atlantic acted less to divide than to act as a religious bridge and market.

… There is a prevailing providentialism amongst Americans of this era: a strong sense that they are operating under God, that God intervenes in human history, and that one has to read the times in the light of God’s Word. It goes some way to understanding the sources of the sacrificial imperative that I’ve mentioned.

A. Lincoln had much the same troubled attitude toward the evangelicals as Jefferson. He was unimpressed by Peter Cartwright’s Methodistic revivalism, as well as his Democratic politics.Q. I’m thinking of the Second Inaugural, which is a wonderful speech, in which he refers to both the North and the South praying to the same God. And maybe this is one of these moments where Lincoln is being ironic?

A. Mark Noll rightly says that the most profound theological statement of the Civil War was when Lincoln noted that both sides pray to the same God, that God cannot be on the side of both—and then reflects that “it is quite possible that God’s purpose is something different from the purpose of either party.” This is what he writes in a private document, “Memorandum on the Divine Will,” dating from 1863 or 1864. It’s significant that he now sees the Almighty as a God who mysteriously intervenes in human history, as opposed to the distant creator God, the God of reason, that he himself invoked as a young man. That was the God of Tom Paine, the clockmaker God who sets the universe in motion and then retreats, leaving the machinery to run itself. …RELATED: 1619, Mao, & 9-11: History According to the NYT — Plus, a Remarkable Issue of National Geographic Reveals the Leftists' "Blame America First" Approach to History

• Wilfred Reilly on 1619: quite a few contemporary Black problems have very little to do with slavery

NO MAINSTREAM HISTORIAN CONTACTED FOR THE 1619 PROJECT

• "Out of the Revolution came an anti-slavery ethos, which never

disappeared": Pulitzer Prize Winner James McPherson Confirms that No Mainstream Historian Was Contacted by the NYT for Its 1619 History Project

• "Out of the Revolution came an anti-slavery ethos, which never

disappeared": Pulitzer Prize Winner James McPherson Confirms that No Mainstream Historian Was Contacted by the NYT for Its 1619 History Project

• Gordon Wood: "The Revolution unleashed antislavery sentiments that led to the first abolition movements in the history of the world" — another Pulitzer-Winning Historian Had No Warning about the NYT's 1619 Project

• A Black Political Scientist "didn’t know about the 1619 Project until it came out"; "These people are kind of just making it up as they go"

• Clayborne Carson: Another Black Historian Kept in the Dark About 1619

• If historians did not hear of the NYT's history (sic) plan, chances are great that the 1619 Project was being deliberately kept a tight secret

• Oxford Historian Richard Carwardine: 1619 is “a preposterous and one-dimensional reading of the American past”

• World Socialists: "the 1619 Project is a politically motivated falsification of history" by the New York Times, aka "the mouthpiece of the Democratic Party"

THE NEW YORK TIMES OR THE NEW "WOKE" TIMES?

• Dan Gainor on 1619 and rewriting history: "To the Left elite like the NY Times, there’s no narrative they want to destroy more than American exceptionalism"

• Dan Gainor on 1619 and rewriting history: "To the Left elite like the NY Times, there’s no narrative they want to destroy more than American exceptionalism"

• Utterly preposterous claims: The 1619 project is a cynical political ploy, aimed at piercing the heart of the American understanding of justice

• From Washington to Grant, not a single American deserves an iota of gratitude, or even understanding, from Nikole Hannah-Jones; however, modern autocrats, if leftist and foreign, aren't "all bad"

• One of the Main Sources for the NYT's 1619 Project Is a Career Communist Propagandist who Defends Stalinism

• A Pulitzer Prize?! Among the 1619 Defenders Is "a Fringe Academic" with "a Fetish for Authoritarian Terror" and "a Soft Spot" for Mugabe, Castro, and Even Stalin

• Influenced by Farrakhan's Nation of Islam?! 1619 Project's History "Expert" Believes the Aztecs' Pyramids Were Built with Help from Africans Who Crossed the Atlantic Prior to the "Barbaric Devils" of Columbus (Whom She Likens to Hitler)

• 1793, 1776, or 1619: Is the New York Times Distinguishable from Teen Vogue? Is It Living in a Parallel Universe? Or Is It Simply Losing Its Mind in an Industry-Wide Nervous Breakdown?

• No longer America's "newspaper of record," the "New Woke Times" is now but a college campus paper, where kids like 1619 writer Nikole Hannah-Jones run the asylum and determine what news is fit to print

• The Departure of Bari Weiss: "Propagandists", Ethical Collapse, and the "New McCarthyism" — "The radical left are running" the New York Times, "and no dissent is tolerated"

• "Full of left-wing sophomoric drivel": The New York Times — already drowning in a fantasy-land of alternately running pro-Soviet Union apologia and their anti-American founding “1619 Project” series — promises to narrow what they view as acceptable opinion even more

• "Deeply Ashamed" of the… New York Times (!), An Oblivious Founder of the Error-Ridden 1619 Project Uses Words that Have to Be Seen to Be Believed ("We as a News Organization Should Not Be Running Something That Is Offering Misinformation to the Public, Unchecked")

• Allen C Guelzo: The New York Times offers bitterness, fragility, and intellectual corruption—The 1619 Project is not history; it is conspiracy theory

• The 1619 Project is an exercise in religious indoctrination: Ignoring, downplaying, or rewriting the history of 1861 to 1865, the Left and the NYT must minimize, downplay, or ignore the deaths of 620,000 Americans

• 1619: It takes an absurdly blind fanaticism to insist that today’s free and prosperous America is rotten and institutionally oppressive

• The MSM newsrooms and their public shaming terror campaigns — the "bullying campus Marxism" is closer to cult religion than politics: Unceasingly searching out thoughtcrime, the American left has lost its mind

• Fake But Accurate: The People Behind the NYT's 1619 Project Make a "Small" Clarification, But Only Begrudgingly and Half-Heartedly, Because Said Mistake Actually Undermines The 1619 Project's Entire Premise

• The Truth Is Out: "The 1619 Project Is Not a History," Admits Hannah-Jones, and "Never Pretended to Be"

THE REVOLUTION OF THE 1770s

• The Collapse of the Fourth Estate by Peter Wood: No

one has been able to identify a single leader, soldier, or supporter of

the Revolution who wanted to protect his right to hold slaves (A declaration that

slavery is the founding institution of America and the center of

everything important in our history is a ground-breaking claim, of the

same type as claims that America condones rape culture, that 9/11 was an

inside job, that vaccinations cause autism, that the Moon landing was a

hoax, or that ancient astronauts built the pyramids)

• Mary Beth Norton: In 1774, a year before Dunmore's proclamation, Americans had already in fact become independent

• Mary Beth Norton: In 1774, a year before Dunmore's proclamation, Americans had already in fact become independent

• Most of the founders, including Thomas Jefferson, opposed slavery’s continued existence, writes Rick Atkinson, despite the fact that many of them owned slaves

• Leslie Harris: Far from being fought to preserve slavery, the Revolutionary War became a primary disrupter of slavery in the North American Colonies (even the NYT's fact-checker on the 1619 Project disagrees with its "conclusions": "It took 60 more years for the British government to finally end slavery in its Caribbean colonies")

• Sean Wilentz on 1619: the movement in London to abolish the slave trade formed only in 1787, largely inspired by… American (!) antislavery opinion that had arisen in the 1760s and 1770s

• 1619 & Slavery's Fatal Lie: it is more accurate to say that what makes America unique isn't slavery but the effort to abolish it

• 1619 & 1772: Most of the founders, including Jefferson, opposed slavery’s continued existence, despite many of them owning slaves; And Britain would remain the world's foremost slave-trading nation into the nineteenth century

• Wilfred Reilly on 1619: Slavery was legal in Britain in 1776, and it remained so in all overseas British colonies until 1833

• Not 1619 but 1641: In Fact, the American Revolution of 1776 Sought to Avoid the Excesses of the English Revolution Over a Century Earlier

• James Oakes on 1619: "Slavery made the slaveholders rich; But it made the South poor; And it didn’t make the North rich — So the legacy of slavery is poverty, not wealth"

• One of the steps of defeating truth is to destroy evidence of the truth, says Bob Woodson; Because the North's Civil War statues — as well as American history itself — are evidence of America's redemption from slavery, it's important for the Left to remove evidence of the truth

TEACHING GENERATIONS OF KIDS FALSEHOODS ABOUT THE U.S.

• 1619: No wonder this place is crawling with young socialists and America-haters — the utter failure of the U.S. educational system to teach the history of America’s founding

• 1619: No wonder this place is crawling with young socialists and America-haters — the utter failure of the U.S. educational system to teach the history of America’s founding

• 1619: Invariably Taking the Progressive Side — The Ratio of Democratic to Republican Voter Registration in History Departments is More than 33 to 1

• Denying the grandeur of the nation’s founding—Wilfred McClay on 1619: "Most of my students are shocked to learn that that slavery is not uniquely American"

• Inciting Hate Already in Kindergarten: 1619 "Education" Is Part of Far-Left Indoctrination by People Who Hate America to Kids in College, in School, and Even in Elementary Classes

• "Distortions, half-truths, and outright falsehoods": Where does the 1619 project state that Africans themselves were central players in the slave trade? That's right: Nowhere

• John Podhoretz on 1619: the idea of reducing US history to the fact that some people owned slaves is a reductio ad absurdum and the definition of bad faith

• The 1619 Africans in Virginia were not ‘enslaved’, a black historian points out; they were indentured servants — just like the majority of European whites were

• "Two thirds of the people, white as well as black, who crossed the Atlantic in the first 200 years are indentured servants" notes Dolores Janiewski; "The poor people, black and white, share common interests"

LAST BUT NOT LEAST…

• Wondering Why Slavery Persisted for Almost 75 Years After the Founding

of the USA? According to Lincoln, the Democrat Party's "Principled"

Opposition to "Hate Speech"

• Wondering Why Slavery Persisted for Almost 75 Years After the Founding

of the USA? According to Lincoln, the Democrat Party's "Principled"

Opposition to "Hate Speech"

• Victoria Bynum on 1619 and a NYT writer's "ignorance of history": "As dehumanizing and brutal as slavery was, the institution was not a giant concentration camp"

• Dennis Prager: The Left Couldn't Care Less About Blacks

• The Secret About the Black Lives Matter Outfit; In Fact, Its Name Ought to Be BSD or BAD

• The Real Reason Why Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben, and the Land O'Lakes Maid Must Vanish

• The Confederate Flag: Another Brick in the Leftwing Activists' (Self-Serving) Demonization of America and Rewriting of History

• Who, Exactly, Is It Who Should Apologize for Slavery and Make Reparations? America? The South? The Descendants of the Planters? …

• Anti-Americanism in the Age of the Coronavirus, the NBA, and 1619

No comments:

Post a Comment