|

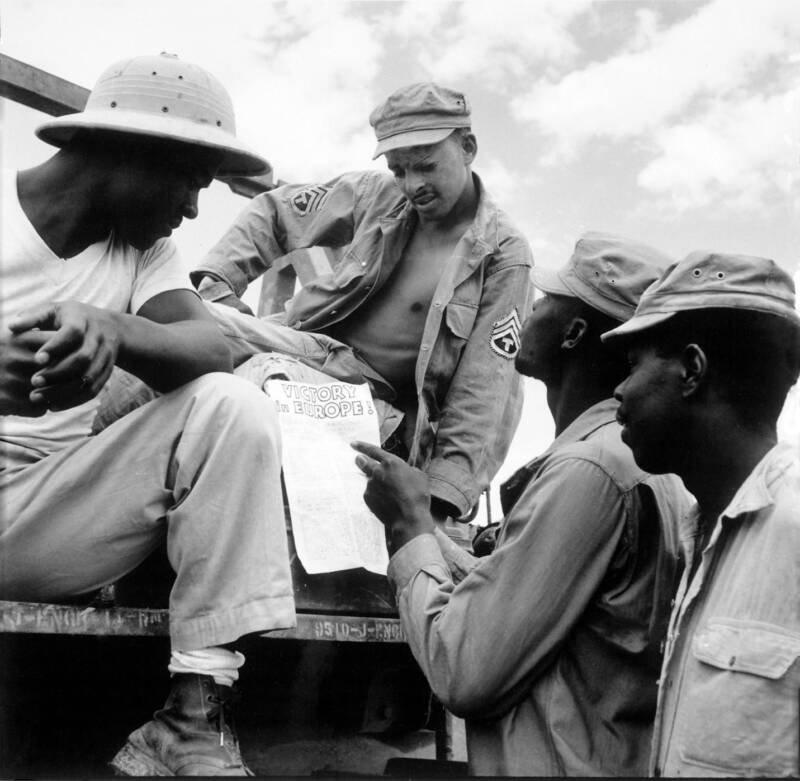

| American soldiers on Okinawa in Japan

listening to the radio broadcast announcing the German surrender and the official end of World War II in Europe. The Battle of Okinawa began in April 1945 and lasted until June, and Japan would not officially surrender until September. (All That's Interesting) |

A shortened version of the following text appeared in the International Herald Tribune of January 9, 1998.

In what is perhaps a laudable attempt to declare that underneath the skin, all humans are basically the same (i.e., equally racist), one of your readers compares the World War II ravages of the Japanese and German armies to the massacre at My Lai. Widespread references to "gooks" notwithstanding, the revelation that more than 300 villagers had been killed in one day in Vietnam by fellow Americans immediately brought about uproar, self-questioning, and opposition in U.S. society, not least in military circles which soundly condemned the massacre. In comparison, the few attempts in the past 60 years to simply present the Japanese nation with a straightforward account of its army's involvement in the slaughter of 300,000 civilians at Nanking and other atrocities have been met with wholesale resistance.Another reader coyly suggests that because they produced the same number of dead, the rape of Nanking is no less racist than the atom bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He overlooks a fundamental difference. The atom bombs did not appear out of the blue, but after years of gruelling fighting, suffering, and dying at the hands of the fanatical armies of the society which passively allowed its soldiers to slaughter civilians, work prisoners of war to death, and otherwise inflict the most cruel atrocities known to modern man.

Unlike the majority of wars which flicker out when the outcome becomes obvious, World War II in the Pacific grew increasingly bloody as U.S. forces approached the Japanese homeland. For instance, the battle for Okinawa, the costliest battle for the Americans — and one of the costliest as well for the Japanese — did not end until June 21, 1945, i.e., after the Germans' surrender in the European theater. The prospect of ever-increasing numbers of dead soldiers, and not racism, was the decisive element in deciding the use of the atomic bombs six weeks later.

In comparison, the Japanese had encountered little effective resistance and few losses in their 1930s occupation of China, and again, at any point during the two-week rape of Nanking, some commander (not least the Emperor) could have stepped in and said "Enough".

More discussion of Hiroshima…

|

| American troops in Burma (now Myanmar) taking a break to read about the Allied victory over Nazi Germany. (All That's Interesting) |

No comments:

Post a Comment